TCA, vol. 61: What happens when non-scientists try to interpret science journals

All the reasons why this might go sideways

The idea for this topic came to me when I was teaching a class called “Medicine and Media” at Georgia State University in 2020. This was a class that analyzed all different kinds of media (movies, TV shows, social media) and how they represented science and influenced people: their attitudes towards medicine and how they interacted with the health care system. And whoo boy, was the timing ever right on this class!

Early in 2020, when COVID-19 was raging and there was no vaccine in sight, unproven treatments like hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin were getting a lot of attention. If you remember, President Trump was very enthusiastic about these drugs, promoted scientific studies that seemed to indicate that they were effective, and downplayed any of their dangers.

I was pretty skeptical of Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) from the jump. As an anti-malarial drug, it works ok (it’s not even the primary choice for malarial infections anymore, with better and less toxic drugs now available). I couldn’t wrap my head around how a drug that stopped a parasite from being able to eat hemglobin could also work against a respiratory virus (but you never know…). But I also knew that the side effects of HCQ could be pretty gnarly. I spoke openly about my concerns on social media, and in response, a neighbor of mine (who is prone to conspiratorial thinking and is anti-science) sent me this article, I think, as a “gotcha” moment.

So, I read the paper. It’s not bad, actually. The science is fine. But I remember thinking: this paper doesn’t really prove that HCQ is an effective treatment for COVID, despite what the title says. Then it dawned on me….. there are so many things in this paper that would trip up a non-scientist and make them come to a different conclusion than I would. I then wrote a whole lecture for my Medicine and Media class about this paper and why non-scientists (especially journalists) can go so completely wrong when reading science literature.

Scientists use English words and phrases differently than you do

What do you think of when you hear the word “significant”? Like if your spouse came home and said “Babe, I got a significant raise at work today!” or your kid told you that they got “a significant amount of candy” when they were trick or treating?

You’d think “a lot”, right?

For us, this word is much much different.

In science, “significant” doesn’t describe the quantity of something, but rather, the quality of something. In this case, the quality of data…..whether or not the data is a “real” effect or just due to chance. Basically, are the data meaningful, or not. So, you can imagine if someone read the above paper and saw the information that ‘the amount of CQ needed to be effective is significantly smaller than for HCQ’ you might think “oh, CQ is a lot more effective than HCQ because you need a much smaller dose!” but then when you actually look at the data, the dose difference is only 2.71 versus 4.51. Meaningful, but not “a lot”.

Another “significant” finding in this paper is that when cells are exposed to CQ, “significantly more” viruses are found in the endosomes (a place where viruses go to die) than when they are exposed to HCQ. What’s the number in this case? 35.3% of viruses versus 29.2%. We’re not talking about astronomical numbers here.

Another particularity in science is that we say things that are factual, but things that you cannot make any inferences from. Take the title of this paper: “Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro”. You might infer that HCQ is safe and non-toxic. However, “less toxic” does not mean “non toxic”. If the title of the paper was “drinking bleach is less toxic than drinking ammonia” it would also be factually correct… but you should not make the inference that drinking bleach is safe.

Science actually speaks Latin, not English.

There are a LOT of science words that are either Latin, or a derivative of Latin (sometimes Greek too, but less so). So, if you were to read this paper, you would come across a lot of Latin words and phrases that might not mean anything to you, and you may just gloss over. Words like: In vitro and cytotoxic. And then there are all the industry terms like: multiplicity of infection (MOI), selectivity index (SI), glycosylation and supernatant. You’d have to look each one of these up, and since there are so many, you’d probably just hope you’d get it from context clues.

But let’s give one very important example from this paper that changes everything: “Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro”

The “in vitro”.

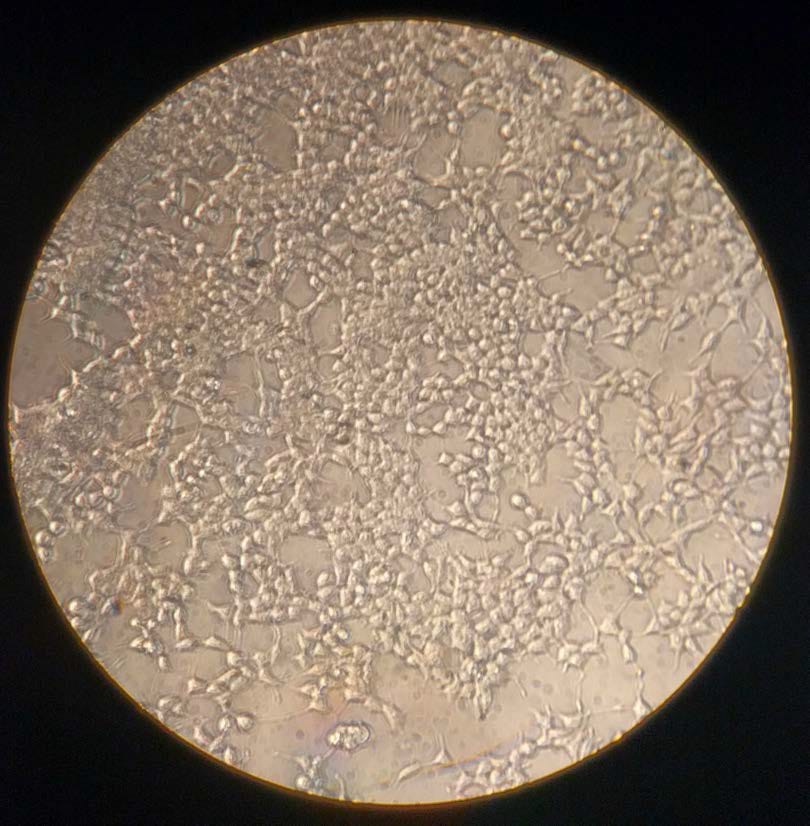

These two contrasting Latin phrases are used a lot in biology: “In vitro” and “in vivo”. Literally translated to “in glass” and “in life”. Experiments that are done “in vitro” are done in test tubes or petri dishes (we don’t actually use glass anymore though). Whereas, experiments that are done “in vivo” are done in living things like plants, animals or people.

So, this paper is showing that HCQ is effective at inhibiting the COVID-19 virus IN A PETRI DISH OF CELLS.

I always get really bothered when I hear reporting of things that kill cancer cells “in vitro”. Like “Honey bee venom kills breast cancer cells”, or “cannabis oil kills leukemia cells”. And then there's the old realiable commentary that somehow Big Pharma is keeping these natural cures away from us.

You know what else kills cancer cells in a petri dish? Fire. Arsenic. Cyanide. Sulfuric acid.

Just because something kills cells in a petri dish (cells attached to a plastic plate, one cell layer thick, with no protection) doesn’t mean that it will work in the complex body of a human, or more importantly…… will be SAFE for the human.

A successful drug, one that eventually makes it to market, must pass several different tests.

Is it effective? Does the drug do what it is supposed to do? In this case, does HCQ stop the COVID-19 virus from replicating?

Is it selective? Does the drug kill the virus but not the human? This is a test for safety and side effects.

Is it bioavailable? Does the drug make it to the site of the infection? For example, if you swallow a pill, does the drug eventually make its way to the lungs to treat the COVID infection?

Is it practical? Is the way that you have to take the drug practical for the average person? For example, if you had to take a pill 12 times a day, every 2 hours, on an empty stomach…. this probably wouldn’t work in real life.

When scientists test drugs for their possibilities, they do it in a very stepwise manner, usually starting with efficacy. If the drug isn’t effective, when why even bother testing specificity, bioavailability or practicality? So, efficacy studies come out first and VERY often, like the paper above. HCQ is being tested for its EFFICACY, not anything else. Often times, when we hear news stories about a drug being effective for something…. but then we never hear about it again, its probably because it failed one of the following tests. A drug is great when it’s effective, but useless if the drug is also toxic to humans (failing the selectivity test).

And that’s exactly what happened to HCQ. The dose of Hydroxychloroquine that is needed to block COVID-19 INSIDE A HUMAN BODY (in vivo) is so high that it’s actually toxic to humans: causing heart, kidney and liver damage. That study came out later… but I bet you didn’t hear about that one on the news.

Not all journals are created equally.

The International Journal of Molecular Biology (open access); The Austin Journal of Pharmacology and Therapeutics; The American Research Journal of Biosciences. Do these all sound legit to you? They all have nice looking websites and publish science articles. But in 2017, they were all caught in a sting operation that exposed the dark underbelly of science publication…. Star Wars-Style. More about that in a second.

The major database for medical journals is called Pubmed, run by the National Library of Medicine. If you wanted to search for a health or medicine related article, that’s where you would go. And you might get the impression that everything you find on Pubmed is reliable and vetted.

They are not.

Pretty much all health/medical articles are catalogued on pubmed, regardless of how good they are. Scientists are actually charged money to publish their articles, and so like everything else, a cottage industry of charlatans has stepped onto the scene to collect as much money as they can from scientists whose data isn’t good enough to get into a reliable journal. There are things called “Predatory journals” which hound scientists for their data, offering them an easy path to publication. For a price.

These journals are not peer-reviewed, or run by experts. Or anyone who actually proofreads the articles, apparently. Because in 2017, a journalist from Neuroskeptic wrote an article called “Mitochondria: Structure, Function and Clinical Relevance”. He sent it to a bunch of different journals, it was accepted by four of them. One demanded $380 dollars to publish it, which he was unwilling to pay, but the other three (the journals listed at the top of this section) DID publish it.

If you read the actual article, which no one at The International Journal of Molecular Biology (open access), The Austin Journal of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, or The American Research Journal of Biosciences could have possibly done…. you would notice that after a few paragraphs the word “mitochondria” turned into “midichlorians” and the paper eventually started talking about the Tragedy of Darth Plagueis the Wise (If you know, you know). The journalist wrote a paper about midichlorians, the imaginary aliens that live inside of a Jedi’s body, from the Star Wars Cannon…. but dressed it up like a science paper. And they published it.

You only had to look at the paper’s authors to know something was up: Lucas McGeorge and Annette Kin.

Ok, so if there are a lot of “fake science papers” floating around out there, how could you possibly know if the one you are reading is legit? Here are some ways to tell:

Is this a reputable, well-known journal in the industry with a high impact factor?

Is the author a trusted and established scientists in the field?

Is it edited by a team of experts?

Has it been peer-reviewed before publication?

Is it a pre-print? (sometimes articles-in-progress are published online before they are peer-reviewed).

So that’s a lot of leg work for a person who is not in the industry to have to do to discover if the article their neighbor sent them on Facebook is legit. But here’s an easy way to do it: Ask a scientist. Someone in the field already knows the reputable journals, the major players and authors to trust, which journals are peer-reviewed. They have already done the leg-work for you…. that’s what expertise does. Trust the experts.

In conclusion.

I’m not saying that normies should stay away from the hard reading, ‘let the adults do the work’ and just trust whatever we say. BUT. Do not think that just because you can read a paper written in English that you can interpret it’s meaning accurately.

In grad school, we spend YEARS learning how to read scientific journals. Like we literally have entire semester-long classes devoted to it. It does not come easily or naturally to anyone, not even someone who has an aptitude for science. Understanding statistical analysis alone is an entire field of biomedicine.

When I had my class (seniors and master’s students in biology) study the paper: “Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro” even a lot of them got it wrong initially.

Also keep in mind that journalists love to report on new exciting efficacy studies without any understanding of all the nuance or the follow-up studies that are needed to determine if a drug is safe and practical. And these things have real-life consequences. After Trump tweeted about HCQ, implying it was some kind of miracle cure, people all over the country tried to buy it online or from inappropriate sources. Chloroquine is also sold in aquarium stores because it can treat fish for parasites. A man actually died from taking aquarium chloroquine, believing it to be as safe as Trump said it was.

NBC News spoke to the wife, who said they learned of chloroquine’s connection to coronavirus during a President Donald Trump news conference, which “was on a lot actually.” They took it because they “were afraid of getting sick,” she said.

“I had (the substance) in the house because I used to have koi fish,” she told the network. “I saw it sitting on the back shelf and thought, ‘Hey, isn’t that the stuff they’re talking about on TV?’”

Stay happy, healthy and informed,

Jessica at TCA

Neuroskeptic. Predatory Journals Hit By 'Star Wars' Sting. Discover. July 2017.